This document contains an exploration of the world of warcraft auction house data. I've been able to use the world of warcraft (WoW) rest-api from blizzard to get a snapshot of all the world of warcraft servers during the mists of panderia expansion timeline. The dataset does not contain any sales but it does contain relevant information on the actual action itself across all world of warcraft servers. Part of the agreement of using the api was that I would be open about any of the findings I've had so that's what I am doing in this blogpost.

The goal of the exploration was to check economic theory. Certain schools of economics require bold assumptions before you can apply any of it's laws and my stance is that these assumptions apply more to world of warcraft than to our world. If (if!) one could show that the laws of economics (whose assumptions fit WoW better) do not fit the data in the WoW dataset then maybe we should consider a complete overhaul of economic theory.

With that attitude, I started exploring this dataset.

WoW, What?

World of Warcraft is kind of a big deal. At it's peak it had 10 million people playing the video game across the world simultaniously. To accomodate this, the creators created multiple servers that could host all the players. These were distributed geographically, as to minimize any lag and to accomodate for all the demand. Every server was the exact same instance of the World of Warcraft, with the only difference being that different players would play in each server.

I cannot stress how big this game was (and still is). The game is so big it even comes with an internal ebay called the auction house where people can trade in-game items for in-game gold. Players can only trade with other players if they are on the same server though, so it is not possible to have an auction available to everybody. Also, in the game there are two opposing sides (the Horde and the Alliance) which have seperate auction houses.

From an economic data perspective this should sound very interesting to study a snapshot of the auction house. To be frank, I am somewhat suprised no academic seems to be seriously discussing the topic of game economies. We have 100s of servers where this is being played with millions of people participating in economic interactions. The data that we collect is from actual humans making actual economic decisions and should be of exellent quality (no noise and complete). The downside of a snapshot of the auction house is that it only tells the story of the supply side. We won't measure actual auction transactions but mere sellers.

The main interesting question that arises; can we speak of price equilibrium across these different servers?

Some initial exploration

Before doing anything serious, I usually fiddle around with small hypotheses to make sure that I understand the dataset well enough. So before diving deep in the price-equilibrium, let's explore a bit.

Let's start by looking at a screenshot of the auction house.

Notice that there are two values bid and buyout. The buyout price is a price you can pay such that you can immediately buy the listed product, the bid price is the price at the moment. I'll use the buyout value of the item as a price because I feel that it most resembles the price from the supply side.

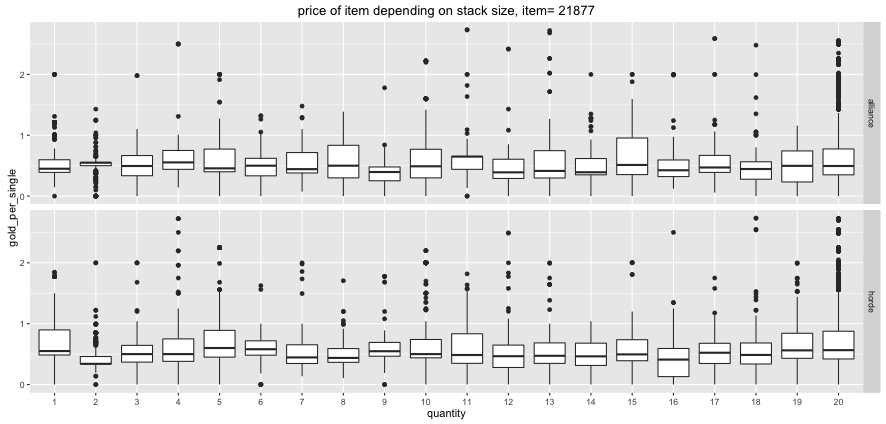

You'll also notice that you can buy a stack of items instead of a single item. At the time of acquiring the data it was possible to get a stack of max 20 but now this has been changed to a stack of 100. I've noticed that the number of items in a stack tends not to influence the price too much. An example boxplot of stacksizes and prices is shown below;

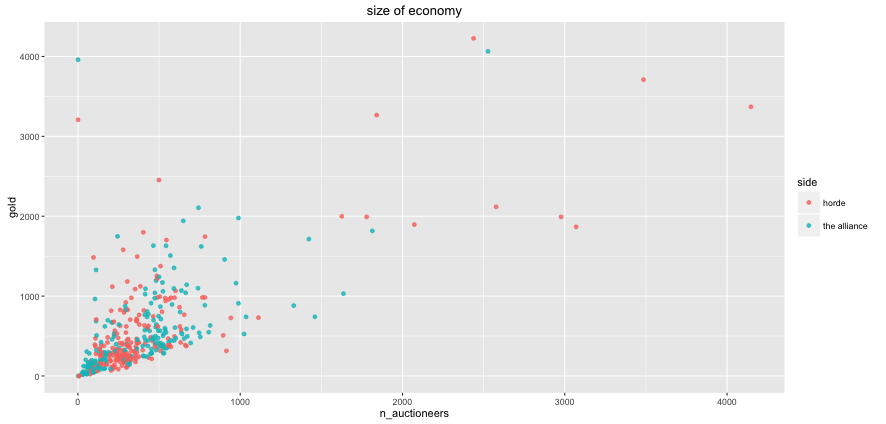

There are differences between servers, even though they all have the exact same game on it. The main difference that should influence the behavior of players on a macro level is the number of players on a server. The refresh rate of collectible items is constant so more players would cause items to be more rare. Below is a scatter plot of total buyout gold (in 1000s) on the server vs. number of auctioneers to show how this can vary. Each point indicates a sererate horde or alliance auction house, one for each server.

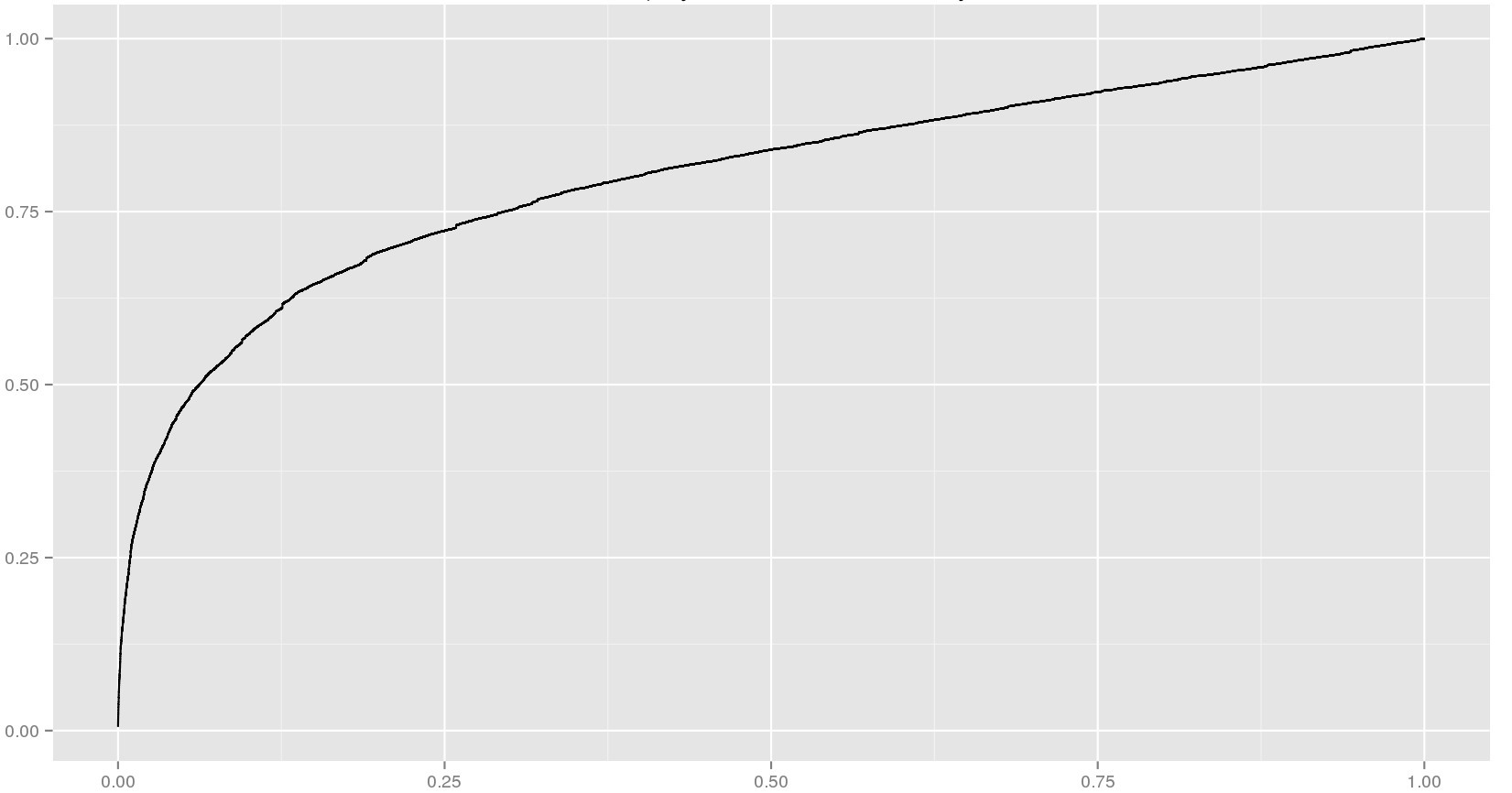

You can also do some more silly queries just for the fun of it. Turns out that the 1% of world of warcraft auction house owns about 25% of it.

Some economic theory

Before moving on to the big query, I just want to mention three economic assumptions that I think apply to world of warcraft better than the real world;

- people have rational preferences when they trade

- individuals maximize utility

- people act independently on the basis of full and relevant information

I find it hard to claim that these assumptions hold in the real world. But if people accept that we can apply economic theory in the real world based on these assumptions then it seems appropriate we can also do so in the world of warcraft.

Being a video game, world of warcraft has a defined goal that players chase and players are rewarded if they get better at it, much more than in our world. Every aspect of the world is documented and quantified, much more than in our world. The assumption of rational players maximizing utility based on perfect information actually makes some sense here.

With these assumptions met, I would assume that auction houses adhere to some kind of price equilibrium. Let's see if that is the case.

Testing Theory

There are different items in the world of warcraft, some of them rare and some of them more common. In order to zoom in on commodity items I'll focus on the top 150 most popular items.

The metrics I'll focus on are the mean buyout price per server and the number of items from each server from each fraction. I would expect that if there's more items on the server that there'll be a lower mean price. After all, more supply would cause the price to go down.

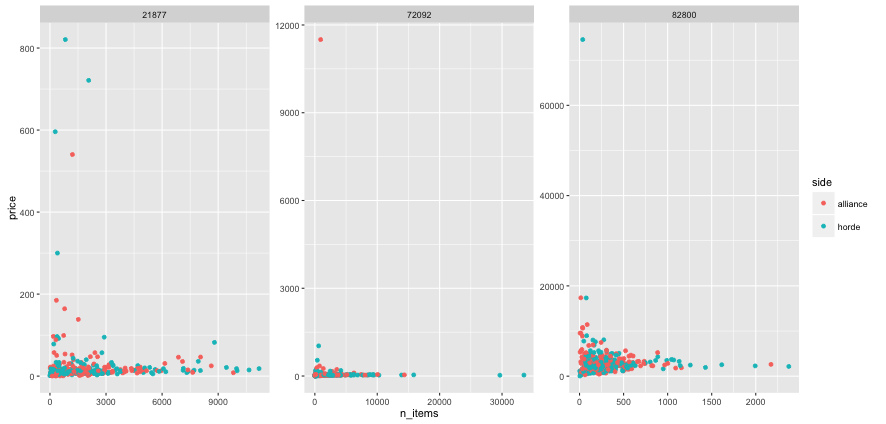

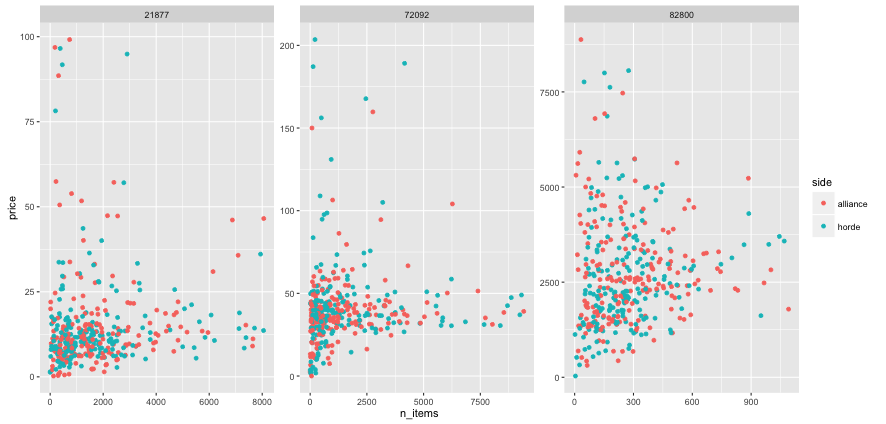

I'll show the supply vs. mean buyout price for three items below.

Note that every point in this chart represents a seperate auction house, from either the horde or the alliance for each server. Also note that the number listed on top of the chart is the item_id (which you could google if you wanted to know what it is). It looks like small quantities on the server might cause higher prices but I am not sure if this is because of outliers or anything else. So I'll remove the 2% outliers on both axis and get this;

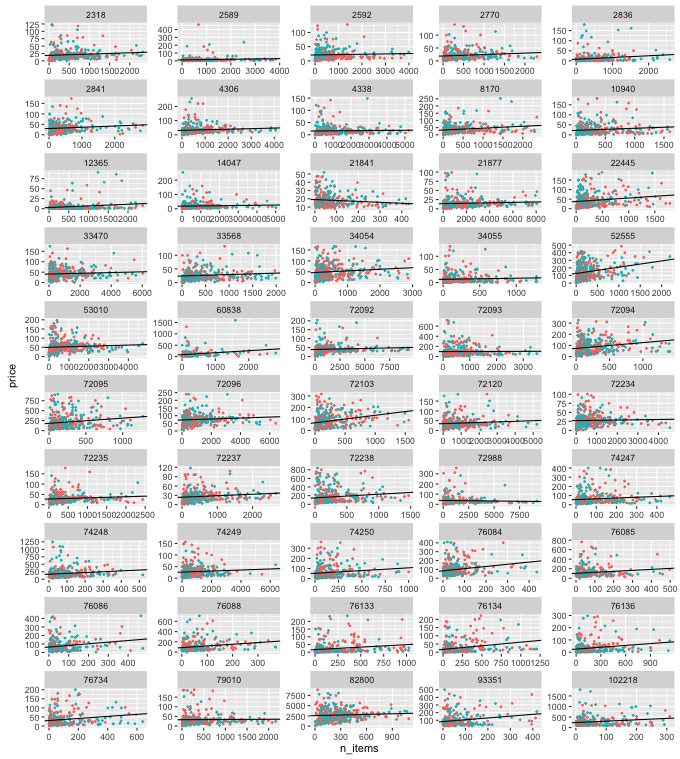

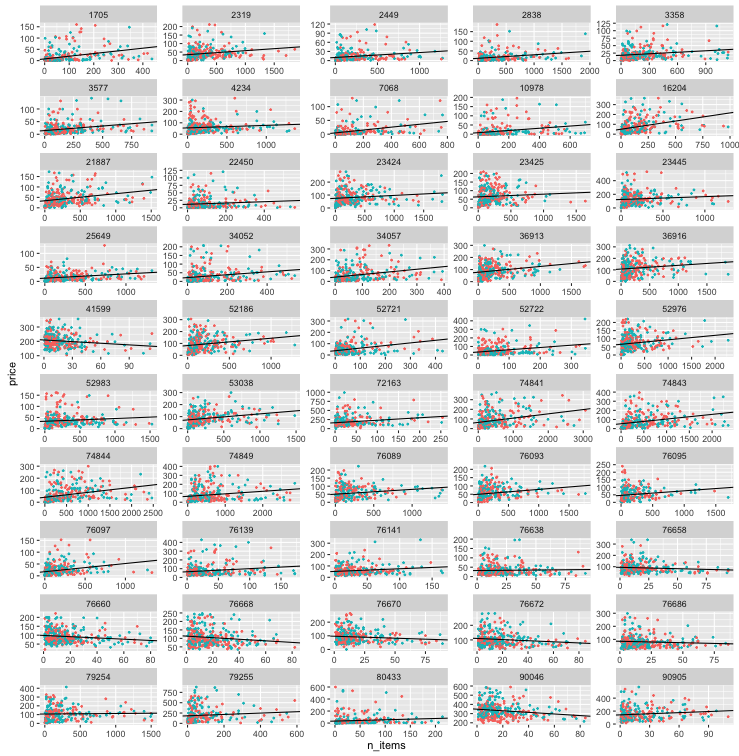

It still is not obvious what the relationship is between number of items and mean price of an item. So how about instead of looking at it we'll do a bit of math. Let's run a regression on each of these sets and check if the $\beta_1$ coefficient is negative where $\beta_1$ is;

$$ \beta_1 = \frac{Cov(x,y)}{Var(x)} $$

In laymans terms; I'll be calculating the slope of the regression line. If this is negative then there's as hint that an increase of items indeed corresponds with a lower price. When I do this for all the items, this is what it looks like;

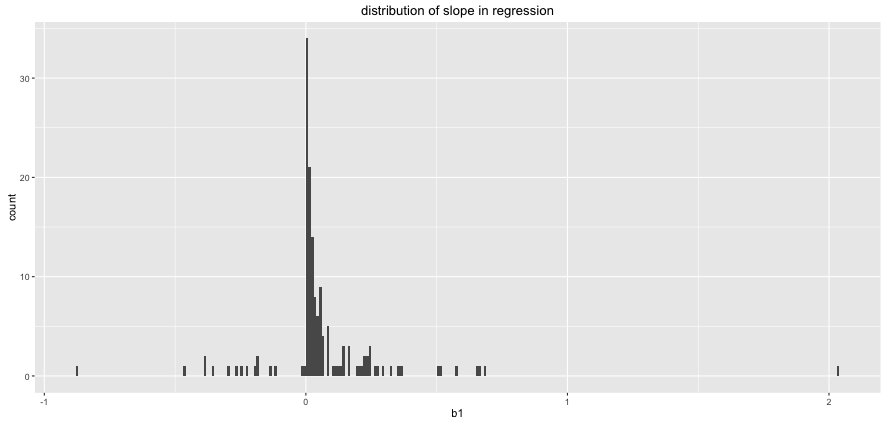

This is very counterintuitive. Larger quantities in the market should proxy towards lower costs per product while it seems like allmost all $\beta_1$ values are near zero or positive. Let's look at the histogram of $\beta_1$ values to be sure.

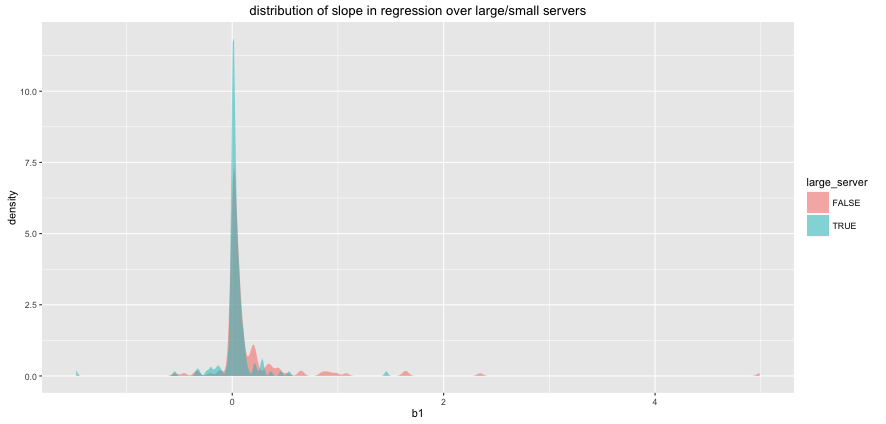

Mhm. No dice. How can we explain this? Truth be told I'm having a hard time figuring this one out (ideas welcome @fishnets88). The main nuance that I could think of was that the number of players on the server might influence the price as well. One can argue that more players might make commidity items more rare because of the in-game refresh rate is constant. When making a split for larger servers based on 50% quantiles and repeating what I've done results in a similar histogram.

One possible interpretation is that the effect supply of supply is moderate and one might use this as an argument for price equilibrium.

Other than that, it might also just be that economics doesn't add up in practice.

Ending Thoughts

The results of what I've seen here seem very odd to explain if you look at it from a economic textbook perspective. I may have been blunt in my approach and there may be some way to explain why an increase in supply equates to an increase in price.

Either way, it seems fine to take the field of economics with a grain of salt.